Spirit and Flesh

INTERVIEW / FEATURE. June 2016.

Spirit and Flesh

INTERVIEW

INTERVIEW

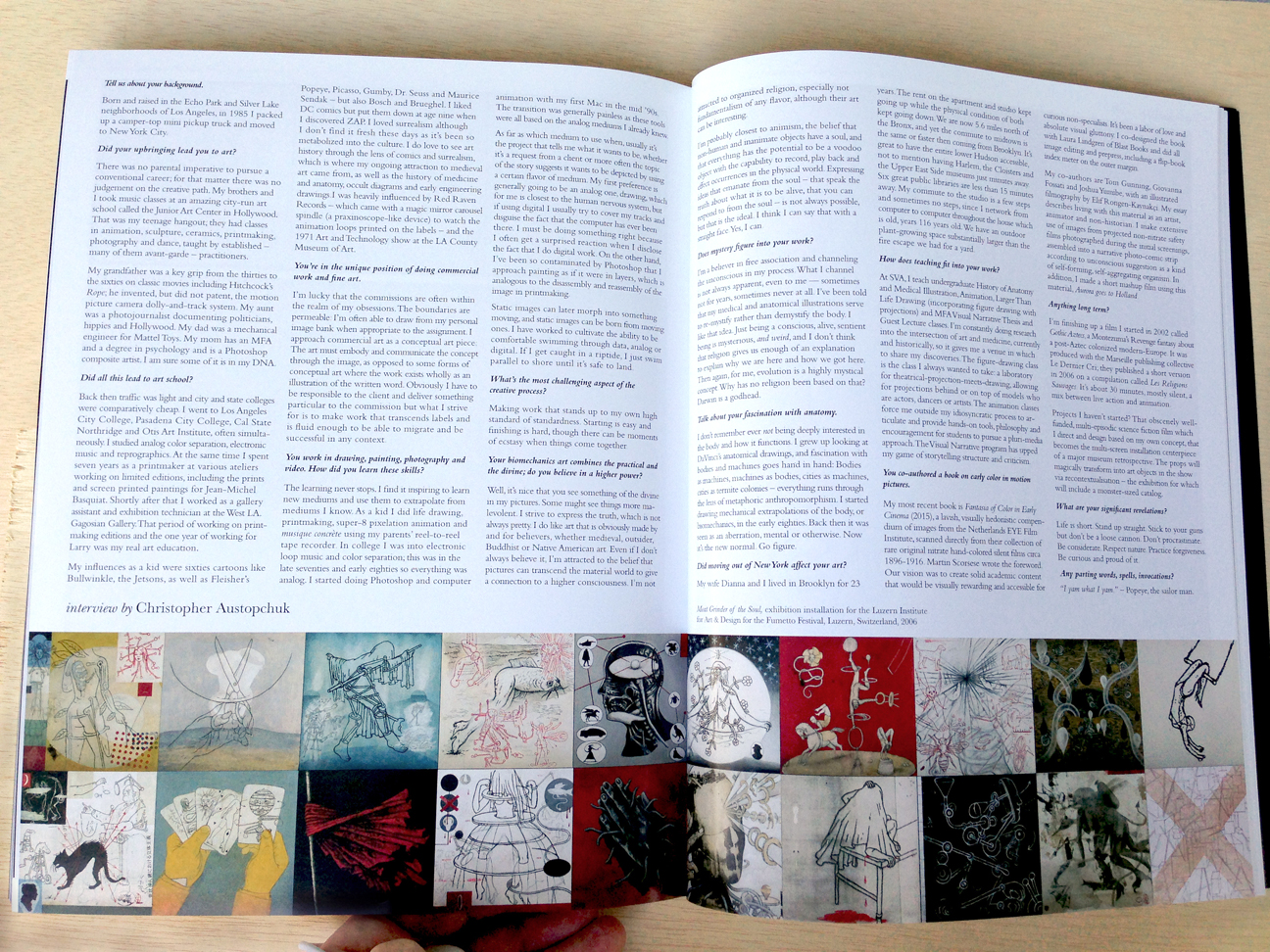

Tell us about your background.

Born and raised in the Echo Park and Silver Lake neighborhoods of Los Angeles, in 1985 I packed up a camper-top mini pickup truck and moved to New York City.

Did your upbringing lead you to art?

There was no parental imperative to pursue a conventional career; for that matter there was no judgement on the creative path. My brothers and I took art classes at an amazing city-run art school called the Junior Art Center in Hollywood.

That was my teenage hangout; they had classes in animation, sculpture, ceramics, printmaking, photography and dance, taught by established - many of them avant-garde - practitioners. My grandfather was a key grip from the thirties to the sixties on classic movies including Hitchcock’s Rope; he invented, but did not patent, the motion picture camera dolly-and-track system. My aunt was a photojournalist documenting politicians, hippies and Hollywood. My dad was a mechanical engineer for Mattel Toys. My mom has an MFA and a degree in psychology and is a Photoshop composite artist. I am sure some of it is in my DNA.

Did all this lead to art school?

Back when traffic was light and city and state colleges were comparatively cheap. I went to Los Angeles City College, Pasadena City College, Cal State Northridge and Otis Art Institute, often simultaneously. I studied analog color separation, electronic music and reprographics. At the same time I spent seven years as a printmaker at various ateliers working on limited editions, including the prints and screen printed paintings for lean-Michel Basquiat. Shortly after that I worked as a gallery assistant and exhibition technician at the West LA. Gagosian Gallery. That period of working on printmaking editions and the one year of working for Larry was my real art education.

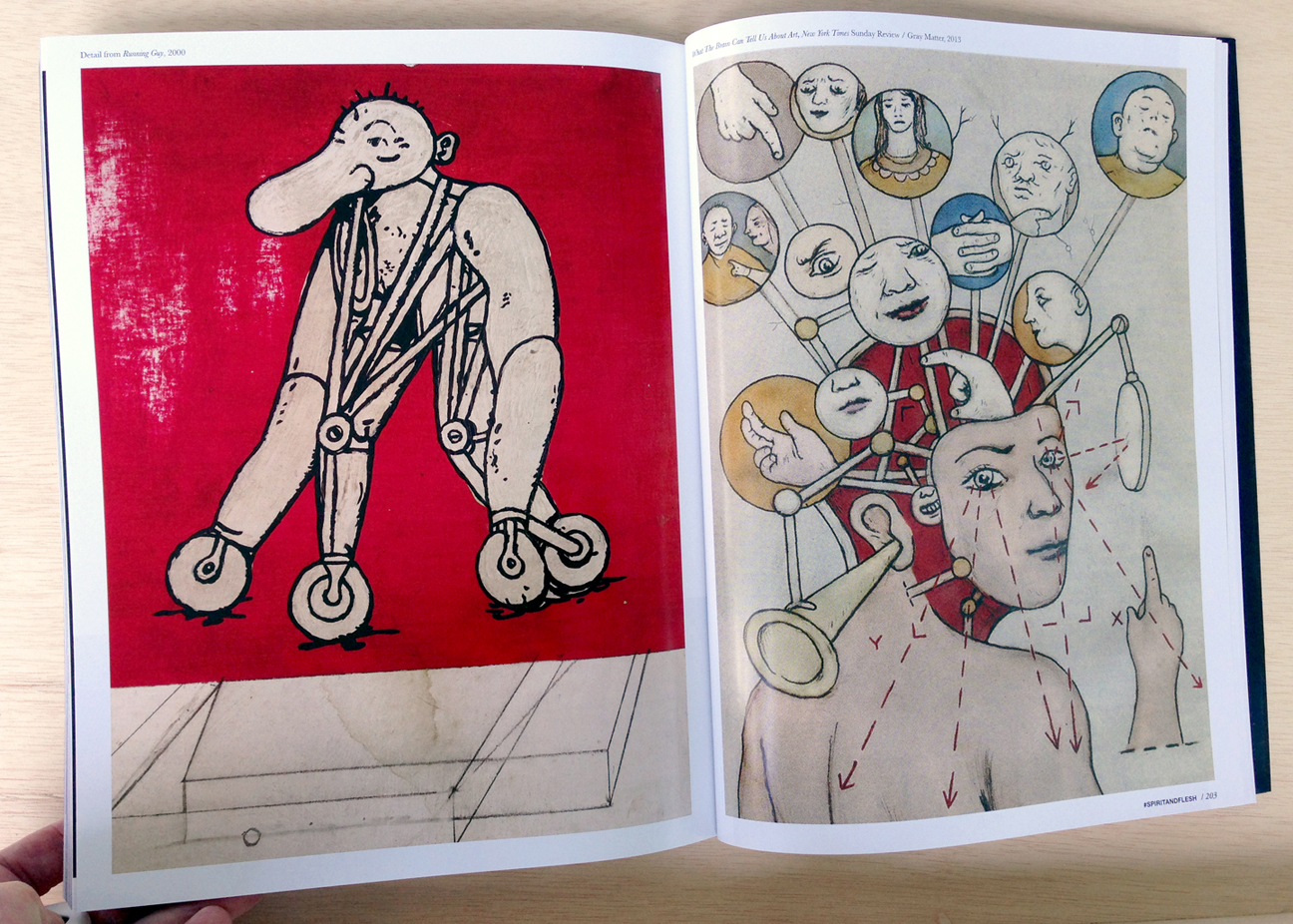

My influences as a kid were sixties cartoons like Bullwinkle, the Jetsons, as well as Flesher’s Popeye, Picasso, Gumby, Dr. Seuss and Maurice Sendak - but also Bosch and Brueghel. I liked DC comics but put them down at age nine when I discovered ZAP. I loved surrealism although I don't find it fresh these days as it's been so metabolized into the culture. I do love to see art history through the lens of comics and surrealism, which is where my ongoing attraction to medieval art came from, as well as the history of medicine and anatomy, occult diagrams and early engineering drawings. I was heavily influenced by Red Raven Records - which came with a magic mirror carousel spindle (a praxinoscope-like device) to watch the animation loops printed on the labels - and the 1971 Art and Technology show at the LA County Museum of Art.

You're in the unique position of doing commercial work and fine art.

I'm lucky that the commissions are often within the realm of my obsessions. The boundaries are permeable: I'm often able to draw from my personal image bank when appropriate to the assignment. I approach commercial art as a conceptual art piece:

The art must embody and communicate the concept through the image, as opposed to some forms of conceptual art where the work exists wholly as an illustration of the written word. Obviously I have to be responsible to the client and deliver something particular to the commission but what I strive for is to make work that transcends labels and is fluid enough to be able to migrate and be successful in any context.

You work in drawing, painting, photography and video. How did you learn these skills?

The learning never stops. I find it inspiring to learn new mediums and use them to extrapolate from mediums I know. As a kid I did life drawing, printmaking, super-8 pixelation animation and musique concrète using my parents' reel-to-reel tape recorder. In college I was into electronic loop music and color separation; this was in the late seventies and early eighties so everything was analog. I started doing Photoshop and computer animation with my first Mac in the mid ‘90s. The transition was generally painless as these tools were all based on the analog mediums I already knew.

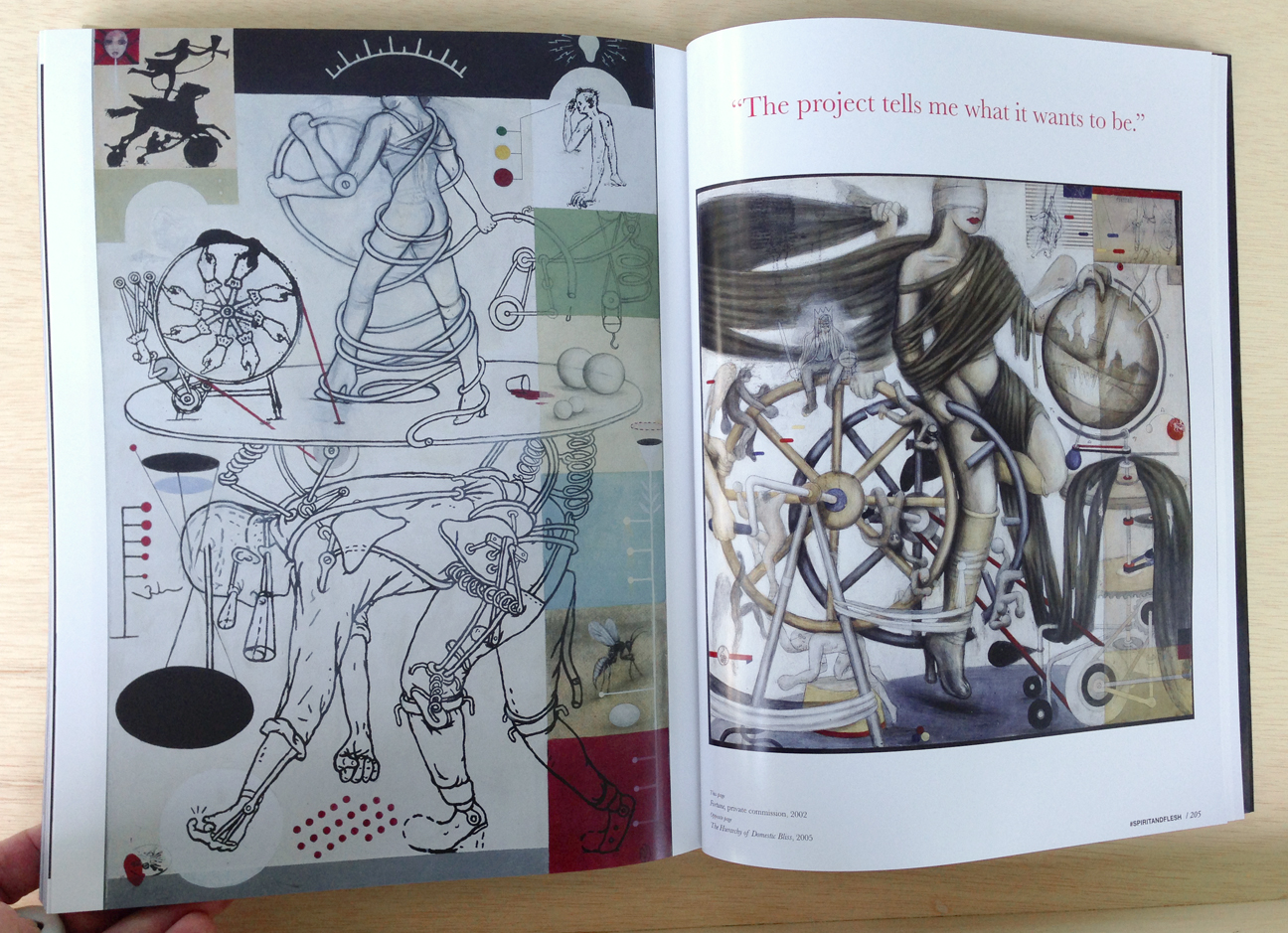

As far as which medium to use when, usually it's the project that tells me what it wants to be, whether it's a request from a client or more often the topic of the story suggests it wants to be depicted by using a certain flavor of medium. My first preference is generally going to be an analog one, drawing, which for me is closest to the human nervous system, but if using digital I usually try to cover my tracks and disguise the fact that the computer has ever been there. I must be doing something right because I often get a surprised reaction when I disclose the fact that I do digital work. On the other hand, I've been so contaminated by Photoshop that I approach painting as if it were in layers, which is analogous to the disassembly and reassembly of the image in printmaking.

Static images can later morph into something moving, and static images can be born from moving ones. I have worked to cultivate the ability to be comfortable swimming through data, analog or digital. If I get caught in a riptide, I just swim parallel to shore until it's safe to land.

What's the most challenging aspect of the creative process?

Making work that stands up to my own high standard of standardness. Starting is easy and finishing is hard, though there can be moments of ecstasy when things come together.

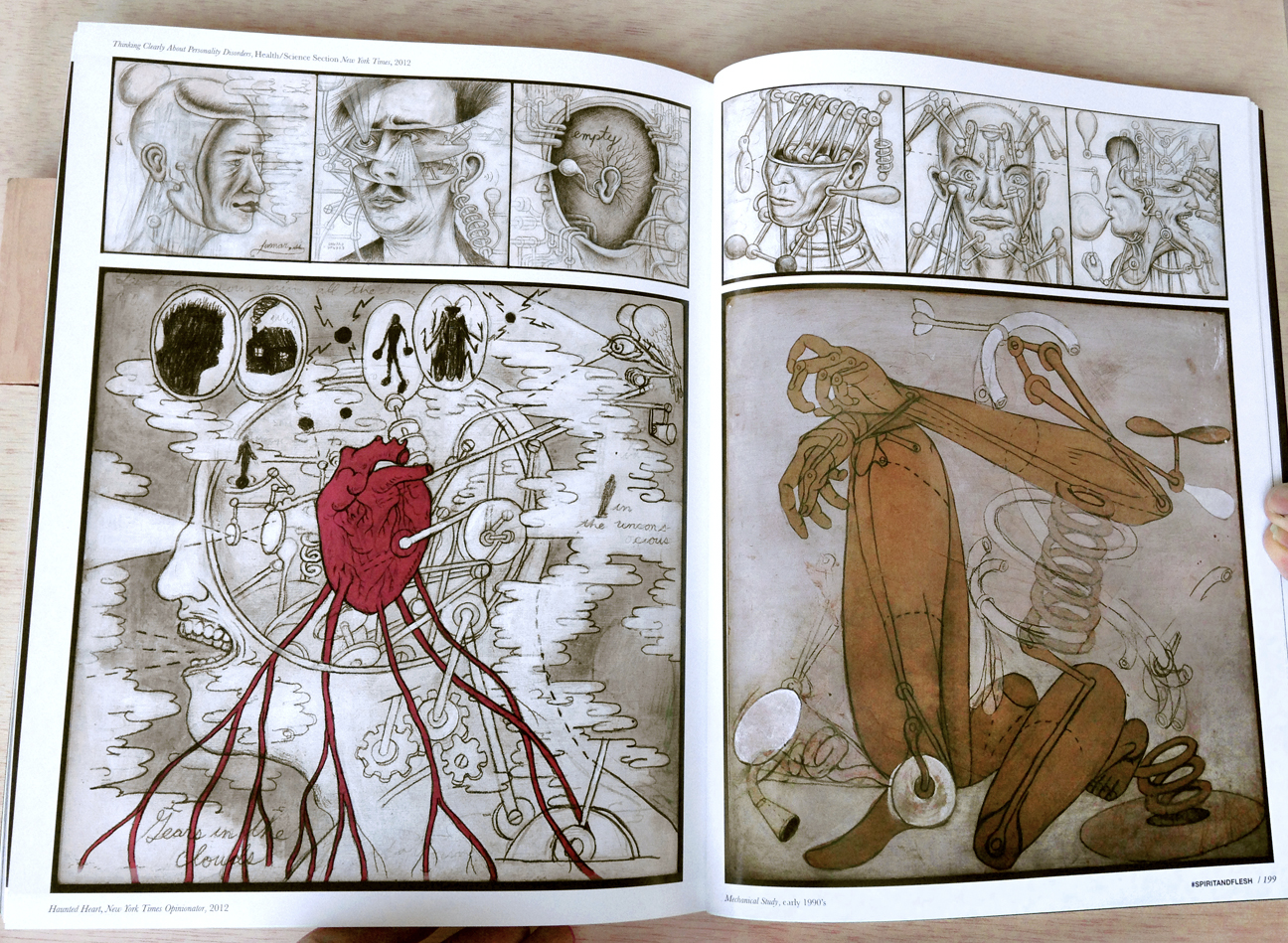

Your biomechanics art combines the practical and the divine; do you believe in a higher power?

Well, it's nice that you see something of the divine in my pictures. Some might see things more malevolent. I strive to express the truth, which is not always pretty. I do like art that is obviously made by and for believers, whether medieval, outsider, Buddhist or Native American art. Even if I don't always believe it, I'm attracted to the belief that pictures can transcend the material world to give a connection to a higher consciousness. I'm not attracted to organized religion, especially not fundamentalism of any flavor, although their art can be interesting.

I'm probably closest to animism, the belief that non-human and inanimate objects have a soul, and that everything has the potential to be a voodoo object with the capability to record, play back and effect occurrences in the physical world. Expressing ideas that emanate from the soul that speak the truth about what it is to be alive, that you can respond to from the soul - is not always possible, but that is the ideal. I think I can say that with a straight face. Yes, I can.

Does mystery figure into your work?

I'm a believer in free association and channeling the unconscious in my process. What I channel is not always apparent, even to me - sometimes not for years, sometimes never at all. I've been told that my medical and anatomical illustrations serve to re-mystify rather than demystify the body. I like that idea. Just being a conscious, alive, sentient being is mysterious, and weird, and I don't think that religion gives us enough of an explanation to explain why we are here and how we got here.

Then again, for me, evolution is a highly mystical concept. Why has no religion been based on that? Darwin is a godhead.

Talk about your fascination with anatomy.

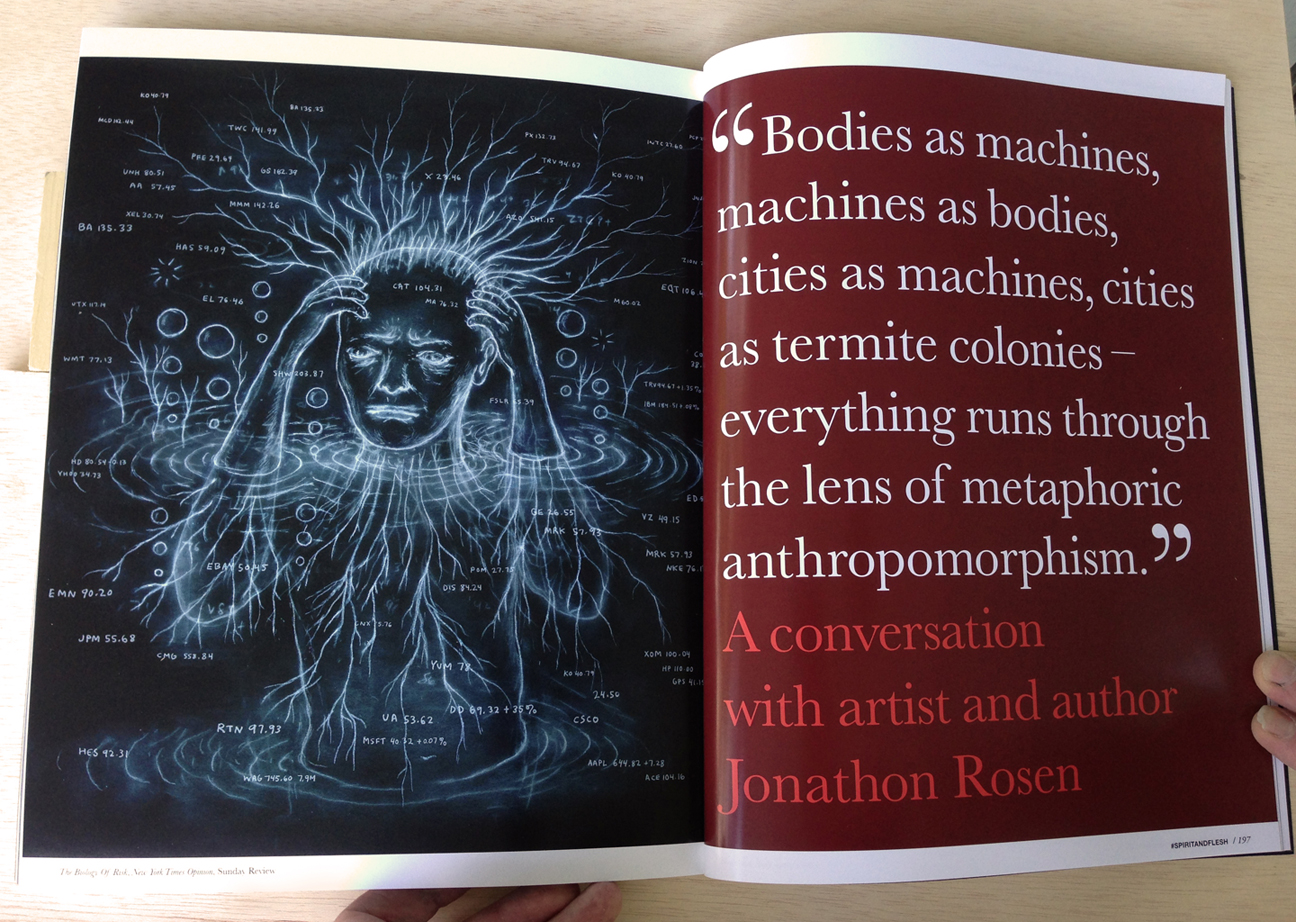

I don't remember ever not being deeply interested in the body and how it functions. I grew up looking at DaVinci's anatomical drawings, and fascination with bodies and machines goes hand in hand: Bodies as machines, machines as bodies, cities as machines, cities as termite colonies - everything runs through the lens of metaphoric anthropomorphism. I started drawing mechanical extrapolations of the body, or biomechanics, in the early eighties. Back then it was seen as an aberration, mental or otherwise. Now it's the new normal. Go figure,

Did moving out of New York affect your art?

My wife Dianna and I lived in Brooklyn for years. The rent on the apartment and studio kept going up while the physical condition of both kept going down. We are now 5.6 miles north of the Bronx, and yet the commute to midtown is the same or faster then coming from Brooklyn. It's great to have the entire lower Hudson accessible, not to mention having Harlem, the Cloisters and the Upper East Side museums just minutes away.

Six great public libraries are less than 15 minutes away. My commute to the studio is a few steps and sometimes no steps, since I network from computer to computer throughout the house which is old, years 116 years old. We have an outdoor plant-growing space substantially larger than the fire escape we had for a vard.

How does teaching fit into your work?

At SVA, I teach undergraduate History of Anatomy and Medical Illustration, Animation, Larger Than Life Drawing (incorporating figure drawing with projections) and MA Visual Narrative Thesis and Guest Lecture classes. I'm constantly doing research into the intersection of art and medicine, currently and historically, so it gives me a venue in which to share my discoveries. The figure-drawing class is the class I always wanted to take: a laboratory for theatrical-projection-meets-drawing, allowing for projections behind or on top of models who are actors, dancers or artists. The animation classes force me outside my idiosyncratic process to articulate and provide hands-on tools, philosophy and encouragement for students to pursue a pluri-media approach. The Visual Narrative program has upped my game of storytelling structure and criticism.

You co-authored a book on early color in motion pictures.

My most recent book is Fantasia of Color in Early Cinema (2015), a lavish, visually hedonistic compendium of images from the Netherlands EYE Film Institute, scanned directly from their collection of rare original nitrate hand-colored silent films circa 1896-1916. Martin Scorsese wrote the foreword.

Our vision was to create solid academic content that would be visually rewarding and accessible for curious non specialists. It's been a labor of love and absolute visual gluttony. I co-designed the book with Laura Lindgren of Blast Books and did all. image editing and prepress, including a flip-book index meter on the outer margin.

My co-authors are Tom Gunning, Giovanna Fossati and Joshua Yumibe, with an illustrated filmography by Elif Rongen-Kaynakçi. My essay describes living with this material as an artist, animator and non-historian. I make extensive use of images from projected non-nitrate safety films photographed during the initial screenings, assembled into a narrative photo-comic strip according to unconscious suggestion as a kind of self-forming, self-aggregating organism. In addition, I made a short mashup film using this material, Aurora goes to Holland.

Anything long term?

I'm finishing up a film I started in 2002 called Gothic Aztecs, a Montezuma's Revenge fantasy about a post-Aztec colonized modern-Europe. It was produced with the Marseille publishing collective Le Dernier Cri; they published a short version in 2006 on a compilation called Les Religions Sauvages. It's about 30 minutes, mostly silent, a mix between live action and animation.

Projects I haven't started? That obscenely well-funded, multi-episodic science fiction film which I direct and design based on my own concept, that becomes the multi-screen installation centerpiece of a major museum retrospective. The props will magically transform into art objects in the show via recontextualisation - the exhibition for which will include a monster-sized catalog.

What are your significant revelations?

Life is short. Stand up straight. Stick to your guns but don't be a loose cannon. Don't procrastinate. Be considerate. Respect nature. Practice forgiveness.

Be curious and proud of it.

Any parting words, spells, invocations?

"I yam what I yam." - Popeye, the sailor man