Daring Little Lady Swing like a Pendulum, Do.

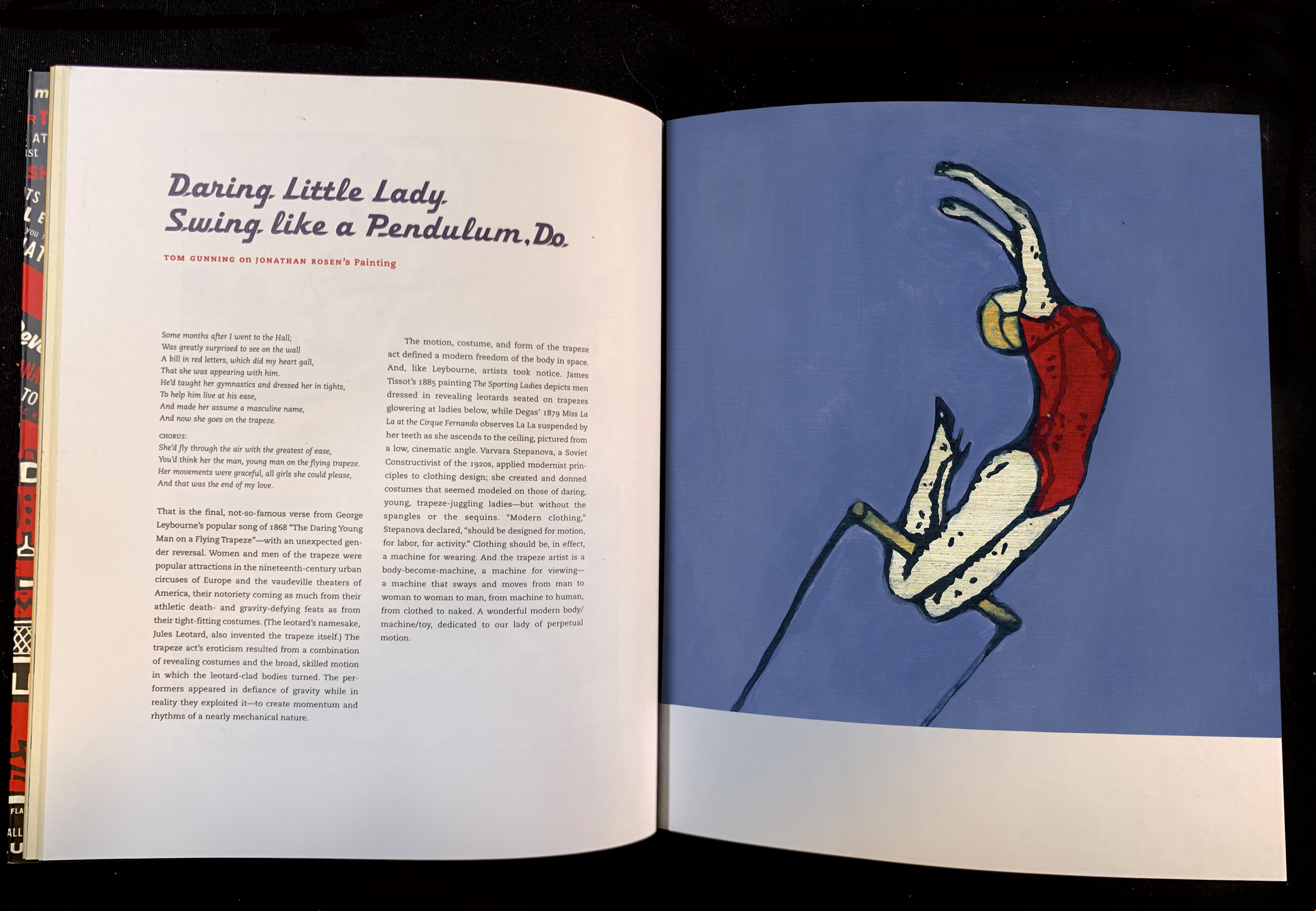

TOM GUNNING on JONATHON ROSEN's Painting ‘Acrobat Girl’.

Tom Gunning is Professor Emeritus of Art History, Cinema and Media Studies, and the College Cinema and Media Studies at The University of Chicago

from the Gansfeld #4 | 2005 / Acrobat girl, collection Dan Nadel

Some months after I went to the Hall;

Was greatly surprised to see on the wall

A bill in red letters, which did my heart gall,

That she was appearing with him.

He'd taught her gymnastics and dressed her in tights,

To help him live at his ease,

And made her assume a masculine name,

And now she goes on the trapeze.

CHORUS:

She'd fly through the air with the greatest of ease,

You'd think her the man, young man on the flying trapeze.

Her movements were graceful, all girls she could please,

And that was the end of my love.

That is the final, not-so-famous verse from George

Leybourne's popular song of 1868 "The Daring Young

Man on a Flying Trapeze"-with an unexpected gen-

der reversal. Women and men of the trapeze were

popular attractions in the nineteenth-century urban

circuses of Europe and the vaudeville theaters of

America, their notoriety coming as much from their

athletic death- and gravity-defying feats as from

their tight-fitting costumes. (The leotard's namesake,

Jules Leotard, also invented the trapeze itself.) The

trapeze act's eroticism resulted from a combination

of revealing costumes and the broad, skilled motion

in which the leotard-clad bodies turned. The per-

formers appeared in defiance of gravity while in

reality they exploited it--to create momentum and

rhythms of a nearly mechanical nature.

The motion, costume, and form of the trapeze

act defined a modern freedom of the body in space.

And, like Leybourne, artists took notice. James

Tissot's 1885 painting The Sporting Ladies depicts men

dressed in revealing leotards seated on trapezes

glowering at ladies below, while Degas' 1879 Miss La

La at the Cirque Fernando observes La La suspended by

her teeth as she ascends to the ceiling, pictured from

a low, cinematic angle. Varvara Stepanova, a Soviet

Constructivist of the 1920s, applied modernist prin-

ciples to clothing design; she created and donned

costumes that seemed modeled on those of daring,

young, trapeze-juggling ladies--but without the

spangles or the sequins.

"Modern clothing,"Stepanova declared,

"should be designed for motion,

for labor, for activity." Clothing should be, in effect,

a machine for wearing. And the trapeze artist is a

body-become-machine, a machine for viewing-

a machine that sways and moves from man to

woman to woman to man, from machine to human,

from clothed to naked. A wonderful modern body/

machine/toy, dedicated to our lady of perpetual

motion.